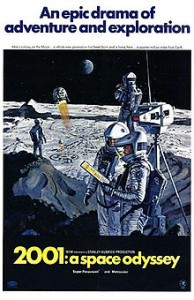

2001: A Space Odyssey ***** (1968, Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood, William Sylvester) – Classic Movie Review 195

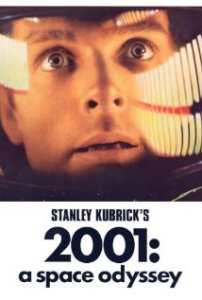

‘Do you read me, HAL?’

‘Affirmative, Dave, I read you.’

Stanley Kubrick’s monumental 1968 sci-fi epic is a gloriously hypnotic, spectacular and ultra-imaginative masterpiece of cinema. It’s a work of genius and a movie milestone. This is the moment the fantasy film went stratospheric – in terms of budget, intellect, imagination and ambition.

A banquet for the brain and a treat for the eyes, 2001 is thrilling, thought-provoking and ultimately mystifying. British made at MGM’s late, much-lamented Borehamwood Studios, it’s also a stupendous tribute to the technicians and talent of the local film industry. No wonder Kubrick came to live in the UK!

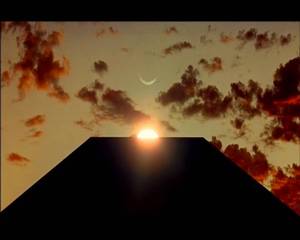

A mysterious, symbolic black slab darts across the time scale. Mankind finds a monolithic artificial object beneath the surface of the Moon. (It was the last movie about men on the Moon before Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin actually got there.)

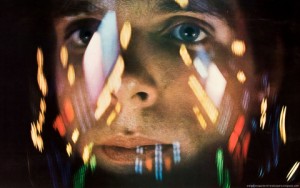

Spacemen Dr Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Dr Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood) set out on a quest to find those who sent the monolith there years ago. On their journey to Jupiter, they enjoy the aid (or hindrance) of a honey-toned, super-intelligent computer. H.A.L. 9000 (voiced by Douglas Rain, replacing Martin Balsam and Nigel Davenport, who had both recorded it and been rejected by Kubrick as respectively having too much emotion and being too British). H.A.L. – that’s heuristic algorithmic computer, incidentally.

Early man has found one of those darned monoliths on Earth too, by the way, as revealed in the Dawn of Man sequence. Did I mention the monkeys? Apart from two baby chimps, they’re all very obviously played by human actors in costume. Comedian Ronnie Corbett was used as a makeup model, but sadly he isn’t in the final movie!

That’s daring, exciting stuff and the film’s musically daring too. Dumping Alex North as soundtrack composer, Kubrick goes for all classical music instead. Johann Strauss’s 1866 waltz The Blue Danube accompanies the planetary journeys. What an odd idea this was, but how perfectly it’s turned out. The famous 2001 theme is Richard Strauss’s 1896 Also Sprach Zarathustra (Karl Boehm’s Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra). The soundtrack album was going to go ballistic in the LP charts.

Kubrick courted Arthur C Clarke for the project via an MGM executive back in 1963 when he sent a telegram saying: ‘Stanley Kubrick interested in doing film on ETs. Are you interested? Thought you were recluse.’ Though it’s basically the story of evolution, Clarke’s plot (based on a total rehash of his old 1948 story The Sentinel) and purpose and the inner workings of 2001 remain teasingly hard to fathom.

That was they way they wanted it. Clarke later said: ‘If you understand 2001 completely, we failed. We wanted to raise far more questions than we answered.’ He and Kubrick worked their way through endless numbers of old space movies, especially those of George Pal, and most notably Conquest of Space (1955), to come up with ideas for the final screenplay, which they wrote and re-wrote endlessly. It finally bears little real resemblance to The Sentinel as its Oscar nomination for Best Original Writing implies.

Thanks to their provocative, head-banging script, combined with the film’s marvellously otherworldly atmosphere and the incredible visual effects and production and set designs (production designers Anthony Masters, Harry Lange, Ernest Archer), this must-see space odyssey is an absolutely astounding journey. An obsessive Kubrick evidently relishes sharing his joy in his most amazingly painstaking attention to detail and his mastery of every aspect of the movie business, showing he is one of cinema’s ultimate film-studio technicians, in the tradition of Hitchcock, Lean, later inspiring a new generation of film-makers in Spielberg, Scorsese and Coppola.

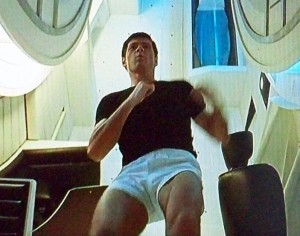

The main Discovery set is brilliant, still the prototype for spaceship interiors for most sci-fi movies. It was built at a huge $750,000 cost by the Vickers-Armstrong plane-makers inside a 12 by two-metre drum designed to rotate at five km per hour.

That’s an amazing achievement both technically and imaginatively, but perhaps most astounding of all still, naturally, are the Oscar-winning Best Special Visual Effects. Created against almost impossible odds in the pre-CGI era of course, they are still totally awesome. Kubrick aside, Douglas Trumbull is the main hero here, as the film’s main special photographic effects supervisor. Wow!

Trumbull said the footage shot was 200 times that of the movie. Extraordinarily, all the effects were printed on the original negatives for maximum visual quality. Kubrick was right about that, too.

Kubrick, who had masterminded the entire look of the film and all the effects as special photographic effects designer and director, personally took the Oscar, though he was not there to collect it on Academy Awards night. However, many of the technicians felt aggrieved that they did not share in the award. Wally Veevers, Tom Howard and Con Pederson were other key visual artists involved as special photographic effects supervisors.

The Oscar for best special visual effects turned out to be the film’s only Oscar, though it had three other nominations, for best direction, best writing (original story and screenplay), and art direction (John Hoesli)/set decoration (Robert Cartwright). The art direction, the marvellous cinematography by Geoffrey Unsworth (double Oscar-0winner for Tess and Cabaret) and sound editor Winston Ryder’s soundtrack were all honoured at the Baftas. But nominated Kubrick didn’t win Best Film.

Perhaps a risky venture for even for a big, successful studio like MGM, 2001 cost a gob-smacking $10,500,000 back in the day, but took back five times that cost in the US alone. After poor previews and slow early box-office, it picked up its audience and soon effortlessly connected with the hippie drug culture of the era. Its Star Gate sequence was a magnet for young drug users at the time and it was even cheekily advertised as ‘the ultimate trip’.

Kubrick said: ‘Dialogue is not essential – that’s part of the medium’s beauty. Check 2001 – 40 minutes of dialogue in a two hours-plus film.’ Check it: it’s 25 minutes till the movie’s first words are spoken and there are none in the last 23 minutes, with 88 dialogue-free minutes in all.

The original roadshow version runs 158 minutes, with the original overture, intermission and exit music. After the New York premiere, Kubrick cut his film to 141 minutes for release due to ‘pacing issues’. These 17 minutes of apparently lost footage were found in pristine, perfectly preserved condition in a salt mine in Kansas by Warner Bros in 2010. But they announced the shortened version was Kubrick’s preferred final edit and that they had no plans to expand or revise the film. It’s time we saw the extended version, guys.

Poor Rock Hudson was one of around 250 people who walked out of the New York premiere, saying: ‘Will someone tell me what the hell this is about?’

After months of experiments, the floating pen effect was just a pen taped to a sheet of glass suspended in front of the camera.

Sequel: the 1984 film 2010: The Year We Made Contact, directed by Peter Hyams, with Dullea and Rain reprising their roles.

2001: A Space Odyssey returns to UK cinemas nationwide on 28 November 2014 in a magnificent digital transfer of the movie by Warner Bros, looking and sounding amazing. It’s the roadshow version, with the original overture, intermission and exit music.

Douglas Rain, who voiced the soft-spoken Hal 9000 robot that went rogue, died on 11 November 2018, aged 90. He voiced Hal again in 2010: The Year We Made Contact. Shakespearean actor Rain co-founded the Stratford Festival, Ontario, Canada, in 1952, and performed at the festival for more than 45 years.

© Derek Winnert 2013 Classic Movie Review 195

Check out more reviews on http://derekwinnert.com/