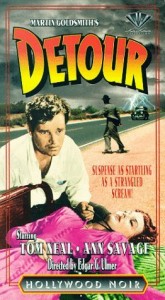

Detour ***** (1945, Tom Neal, Ann Savage, Claudia Drake, Edmund MacDonald) – Classic Movie Review 1547

‘Fate or some mysterious force can put the finger on you or on me for no good reason at all.’ Edgar G Ulmer’s all-time great, flashback-driven 1945 film noir thriller Detour is a deservedly celebrated cult B-movie classic.

Director Edgar G Ulmer’s all-time great, flashback-driven 1945 film noir thriller Detour is a deservedly famous cult B-movie classic. Zero-budgeted but rousingly handled, it is termite art. It holds the honour of being the first B-movie chosen by the Library of Congress for its National Film Registry (in 1992) and it is the first Hollywood film noir so honoured.

Tom Neal plays a broke New York nightclub pianist called Al Roberts, who is hitching a lift west to join his singer girlfriend Sue (Claudia Drake) in Hollywood. He is picked up by a sleazy gambler socialite called Charles Haskell Jr (Edmund MacDonald), who treats him to a meal, gets sleepy and hands the steering wheel over to Roberts. On the long drive, a sunny day turns into a rainy night, Roberts pulls over on a quiet road to pull the hood over the convertible, opens the passenger door and Haskell promptly falls out onto the roadside, dead in a bizarre incident.

Neal tips the body over the hillside, takes the dead man’s money and wallet, and afraid of the police, decides to swap identities with the dead guy, who looks sufficiently like him to fool anyone, and continues his drive to Hollywood. He pulls into a Nevada diner, but, driving off again, makes the mistake of picking up crazy, blowsily sexy femme fatale hitcher Vera (Ann Savage), who knows he isn’t Haskell, as he says he is, because Haskell gave her a ride earlier. She accuses him of murder and blackmails him into finishing the ride, getting Haskell’s wallet money, and selling the car and splitting the proceeds.

Detour is a cherished cult item for its rattling pace, energetic pulp-fiction script, crazily tilted camera shots, flashbacks, cynical voice-over narration, an unforgettable femme fatale and the endearingly obvious back projections. Enterprisingly, it was shot quickly in just 28 days, nearly all on a soundstage inside the PRC Pictures film studio. The legendary idea that the film was shot only in one week is just a myth and apparently derives from a casual remark by Ulmer toward the end of his life.

There are mostly just the two locations – the hotel room apartment, and the car in front of a rear projection screen in the studio, as well as sparse mock-ups of the tiny club where Roberts plays and the little café/ bars he visits. But the 28 days’ shooting schedule also included a brief location shoot in Lancaster, California, for the desert scenes, and rear images for the back projections.

Martin Goldsmith bases his crackling screenplay on his own original 1939 novel, with uncredited work by producer Martin Mooney. In the transfer to screen, the main character’s name was changed from Alexander Roth to Al Roberts, and erotic passages were removed, but there is still plenty of smouldering eroticism in the scenes between Al and Vera. The novel and film ends with a similar fatalistic line: ‘God or Fate or some mysterious force can put the finger on you or on me for no good reason at all.’ The film removes the reference to God.

Director of photography Benjamin H Kline films very stylishly, especially considering the circumstances, with shadowy noir cinematography, in good old black and white of course. The estimated budget of only $30,000 was so small that the 1941 Lincoln Continental V-12 convertible driven by Charles Haskell is Ulmer’s own car, which has thus gone into honourable posterity. It is quite a star of the movie. Also Savage’s sweater belonged to the director’s wife Shirley Ulmer, the film’s script clerk. The sweater was pinned in places to fit the actress more snugly, and the pins can be seen in some shots.

[Spoiler alert] Unfortunately, there is a slight flaw in the disappointing end of the film with the Highway Patrol’s arrest of Al, which enforced by censor Joseph Breen of the Production Code Administration. This was not in the original script and nor was Al’s accidental strangulation of Vera, which Ulmer devised just before filming.

The attentive, inventive soundtrack by Leo Erdody, who had worked with Ulmer on Strange Illusion (1945), is another huge asset. Erdody was also recorded and filmed playing two classical piano pieces – Frédéric Chopin’s ‘Waltz No. 7 in C# minor’ and Johannes Brahms’s ‘Waltz Op. 39 no. 15 in Ab Major’ . As Tom Neal ‘performs’ the piano pieces during scenes in the Break of Dawn nightclub, it is Erdody’s hands that can be seen playing the Brahms in close-up.

There is more excitement with the sharp, incisive editing. Savage recalled that great care was taken during post-production of Detour. The final film was tightly cut down from a much-longer script, which had been shot with more extended dialogue sequences.

Detour provoked one film critic back in 1945 to write: ‘Passion joins with folly to produce termite art par excellence.’

It is one of those many movies where the failure of the original copyright holder to renew the film’s copyright resulted in it falling into public domain, so virtually anyone could duplicate and sell a VHS/ DVD copy of the film. Many versions of the film are edited and/ or of poor quality, having been duped from copies of the film. It is freely available for viewing online.

It was restored by the Academy Film Archive in 2018, and in April 2018 the 4K restoration premiered in Los Angeles at the TCM Festival. A Blu-Ray and DVD was released in March 2019 from the Criterion Collection.

It was remade as Detour in 1992 with Tom Neal Jr playing his father’s old part in a quite effective, close colour remake.

Savage called her 2010 autobiography Savage Detours. She said: ‘The part in Detour seemed like the opportunity every actress longs for. When I first read the script by Martin Goldsmith, I knew that I was going to be part of something very exciting.’ She and Neal were a screen team, having previously made three movies together at Columbia Pictures. They went on to make five movies together. But, she said, Neal put his tongue in her ear on the set and she retaliated by slapping his face as hard as she could. After that, they didn’t speak to each other except when filming scenes.

Tom Neal died in 1972, the same year as Ulmer, but Ann Savage lived long enough to enjoy new-found acclaim both for herself and the movie. During the 70s, 80s and 90s, she flew planes, worked as a lawyers’ clerk and made public appearances with her own personal print of Detour. Ann Savage (aka Bernice Maxine Lyon) died in her sleep on , aged 87.

She was named an icon and legend by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 2005. In May 2007, Time magazine applauded Savage for her body of work and named her walking nightmare portrayal of Vera as one of the Top 10 All-Time Best Villains, alongside James Cagney in White Heat (1949) Robert Mitchum in Cape Fear (1962) and Arnold Schwarzenegger in The Terminator (1984).

In 1951, former college boxer Tom Neal smashed actor Franchot Tone’s cheekbone and nose in a dispute over actress Barbara Payton, leading to Hollywood blackballing Neal.

In 1961, Tom Neal married for the third time, to Gale Bennett. Four years later, he shot her in the back of the head with a .45-caliber gun, killing her instantly. He was brought to trial for her murder but convicted of involuntary manslaughter and sentenced to ten years in prison, serving six. On 6 December 1971, he was released on parole but less than a year later on 7 August 1972 he died of heart failure in North Hollywood aged 58.

Ulmer is also remembered for The Black Cat (1934), The Strange Woman (1946) and Ruthless (1948).

© Derek Winnert 2014 Classic Movie Review 1547

Check out more reviews on http://derekwinnert.com/