Strangers on a Train ***** (1951, Farley Granger, Robert Walker, Ruth Roman, Leo G Carroll, Patricia Hitchcock, Marion Lorne, Howard St John) – Classic Movie Review 68

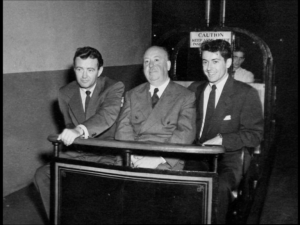

Farley Granger and Robert Walker star as strangers who meet on a train, in the inspired 1951 Alfred Hitchcock suspense thriller Strangers on a Train. One is a psychopath who suggests they exchange murders so neither will be caught.

The inspired 1951 Alfred Hitchcock classic American psychological thriller film noir Strangers on a Train is quite simply the movie suspense thriller by which all others must be judged.

Farley Granger and Robert Walker star as strangers who meet on a train. Unfortunately, one of them is a psychopath who suggests that they exchange murders so that neither will be caught, and the other semi-agrees just to get rid of him.

After a hiatus in box-office successes, Hitchcock hit one of career highspots when he bought the rights to Patricia Highsmith’s first novel and hired Whitfield Cook to write a treatment, then Raymond Chandler to write a screenplay, and finally Ben Hecht’s assistant Czenzi Ormonde to work on the now-famous murder-swap plot with a homoerotic subtext. Psychologists call it folie a deux.

Chandler became openly combative but completed a first draft, and then wrote a second, but when finally he heard back from Hitchcock in late September 1950, it was his dismissal from the project.

Hitchcock wanted to start from square one with his new writer Ormonde, who had no previous screen credit. At their first script conference, Hitchcock pinched his nose, held up Chandler’s draft with his thumb and forefinger and dropped it into a wastebasket. There were less than three weeks until location shooting was scheduled to start. Ormonde, Hitchcock’s associate producer Barbara Keon and Hitchcock’s wife Alma Reville worked under Hitchcock’s guidance late into most nights, and finished enough of the script in time to send the company East to start filming. The rest of the script was completed by early November 1950.

In the vintage storyline, a suave, handsome tennis ace is approached aboard a train by a luridly-dressed, weaselly creep, who discovers they both have trouble from people in their lives and suggests they swap murders to improve their quality of life. The sportsman thinks he is joking and, only half listening, semi-agrees just to get rid of the other man. But it turns out the other guy’s serious, and there are going to be fatal results.

Hitchcock dazzlingly choreographs the characters and themes of the novel into a spellbinding, multi-layered film, as amusing and entertaining on the surface as it is disturbing and creepy underneath.

The casting is perfect all round, but especially the star duo scintillate. In a brio performance, Robert Walker proves one of the screen’s most brilliantly unhinged psychos as Bruno Antony, while Farley Granger is at his most convincing as Guy Haines, a privileged man whose comfortable cloak of easy confidence starts to wear thin and split asunder as his world turns desperately sour.

They are yin and yang. Bruno reasons: that if Guy could kill Bruno’s hated father (Jonathan Hale), he could bump off Guy’s wife Miriam (Laura Elliott, later known as Kasey Rogers), letting him marry lovely Anne Morton (Ruth Roman). Well, reason isn’t perhaps the right word…

It is to Hitchcock’s credit as well as theirs that both Walker and Granger are playing way above their usual game. Hitch’s favourite actor Leo G Carroll (as Anne Morton’s senator father) and his daughter Patricia Hitchcock (as Anne Morton’s sister Barbara) also appear and Marion Lorne (TV’s Bewitched) is memorable as Bruno’s beloved mother. Howard St John also makes his mark as the police captain.

Some of Hitch’s best, most flamboyant set pieces come in an exhilarating rush: (1) the opening sequence of the men’s arrival on the train seen only at foot level; (2) Walker’s demented demonstration of strangling on the neck of an ageing socialite (Norma Varden); (3) the tense intercutting of Granger’s race-against-time tennis tussle at West Side Tennis Club, Forest Hills, with Walker’s equally desperate efforts to retrieve an incriminating lighter from a drain; (4) a fairground murder seen through the lens of the victim’s spectacles; (5) the climactic chase on an out-of-control fairground merry-go-round ride.

Praise too for Robert Burks’s noir-style black and white cinematography and the Ray Heindorf and Dmitri Tiomkin score. Though sometimes accused of being careless with some details, Hitch here ensures a brilliantly crafted movie.

Hitchcock bid at a literary auction for the novel under an assumed name, and bought it cheap, reputedly only £2000. Highsmith never forgave him but, ironically, it was his film that made her literary name and sparked her career. The book’s a very different cup of tea from the film. A faithful version still awaits if someone can take up the challenge of making it.

Whitfield Cook wove in the homoerotic subtext and changed Bruno from a coarse alcoholic into a dapper, charming mama’s boy. Ormonde, Keon and Reville added the runaway merry-go-round, the cigarette lighter, and Miriam’\s thick eyeglasses.

The character called Bruno Antony in the film is called Charles Anthony Bruno in the book. In the novel, Guy Haines is not a tennis player but a promising architect, and he goes through with the murder of Bruno’s father.

Highsmith initially praised the film: ‘I am pleased in general, especially with Bruno, who held the movie together as he did the book.’ But, later, while still praising Walker’s performance as Bruno, she criticised the casting of Ruth Roman as Anne, Hitchcock’s decision to turn Guy from an architect into a tennis player, and the fact that Guy does not murder Bruno’s father as he does in her novel.

In Chandler’s second draft script, the final shot is Guy Haines institutionalised and bound in a straitjacket.

Carefully restored back in 1998 in a beautiful new black and white print as part of Warner Brothers’ 75th birthday celebrations, and today it both looks and is as fresh and exciting as ever.

An early Preview Version edit of the film, often called the British version although it was never released in Britain or anywhere else, includes some scenes either not in or different from the Final Release Version. A two-disc DVD edition was released in 2004 containing both versions. The Preview Version most prominently omits the final scene on the train.

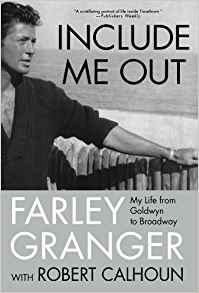

Farley Granger says in his memoir Include Me Out (2007): ‘This film, which after several flops re-established Hitchcock as Hollywood’s master of suspense, is so good that after many years and viewings, I can finally sit back and appreciate my contribution to it.’

Farley interviewed on 25 October 2008 recalled Walker as having great personal problems. ‘He was a wonderful, wonderful actor and I respected him highly.’

In one of his most memorable appearances, Hitchcock puts in his cameo at the start 11 minutes into the film, boarding the train carrying a double bass.

Hitchcock said correct casting saved him ‘a reel of storytelling time’ since audiences would sense qualities in the actors that did not need to be spelled out. That is, apart from Warner Bros’ contract star Ruth Roman, assigned to the film over Hitchcock’s objections. The director found her ‘bristling’ and ‘lacking in sex appeal’ and said that she had been ‘foisted upon me’. Roman became the target of Hitchcock’s scorn throughout filming. Granger diplomatically described it as Hitchcock’s ‘disinterest’ in the actress.

The cast are Farley Granger as Guy Haines, Ruth Roman as Anne Morton, Robert Walker as Bruno Antony, Leo G. Carroll as Senator Morton, Patricia Hitchcock as Barbara Morton, Kasey Rogers as Miriam Joyce Haines, Marion Lorne as Mrs Antony, Jonathan Hale as Mr Antony, Howard St John as Police Captain Turley, John Brown as Professor Collins, Norma Varden as Mrs. Cunningham, Robert Gist as Detective Hennessey, John Doucette as Detective Hammond, Georges Renavent as Monsieur Darville, Odette Myrtil as Madame Darville, Murray Alper as the boatman who recognizes Bruno, and Barry Norton as Tennis Match Spectator.

Strangers on a Train was shot in the autumn of 1950 and released by Warner Bros on June 30, 1951. It cost $1.6 million and earned $7 million.

Farley Granger also stars in Hitchcock’s 1948 Rope.

RIP Farley Earle Granger Jr (July 1, 1925 – March 27, 2011), best known for his two collaborations with Alfred Hitchcock.

Patricia Hitchcock also appears in Hitchcock’s Stage Fright (1950) and Psycho. but Strangers on a Train is her most substantial appearance.

RIP Patricia Alma O’Connell (née Hitchcock; 7 July 1928 – 9 August 2021), the only child of Alfred Hitchcock and Alma Reville. Patricia also appeared in ten episodes of her father’s half-hour TV show Alfred Hitchcock Presents. She was also an extra in her father’s film Sabotage (1936) in the crowd with her mother Alma Reville waiting for and then watching the Lord Mayor’s Show parade.

She was born in London in 1928 and died on 9 August 2021, at home in Thousand Oaks, California, aged 93. Her daughter Teresa Carruba said her mother died in her sleep from natural causes: ‘She was always really good at protecting the legacy of my grandparents and making sure they were always remembered.’

Strangers on a Train is soon to be remade by David Fincher, director of Gone Girl, with a screenplay by Gillian Flynn.

© Derek Winnert 2013 Classic Movie Review 68

Check out more reviews on http://derekwinnert.com