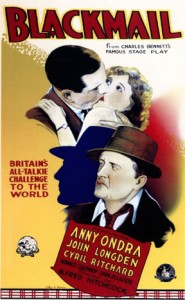

Blackmail ***** (1929, John Longden, Anny Ondra, Cyril Ritchard) – Classic Movie Review 444

Alfred Hitchcock’s lively, imaginative 1929 pioneering thriller film Blackmail is remarkable as Britain’s first talking picture. It’s a treasured relic of a bygone era.

A highly impressive piece of work considering its age and filming difficulties, Blackmail is a slightly rickety but still gripping experience for today’s audiences. It is a striking piece of work visually and of course the quintessential Hitchcock story is still involving because it is very adult, ‘modern’ and full of the director’s disturbing preoccupations.

John Longden stars as Scotland Yard detective Frank Webber, apparently more interested in police work than in his sweetheart Alice White (Anny Ondra), a London shopkeeper’s daughter. Alice has secretly arranged to meet a lecherous artist (Cyril Ritchard) and agrees to go back to his flat to see his studio and be his model for a painting. Instead, he tries to rape Alice, but she defends herself with a bread knife and kills him.

Assigned to a murder case, Frank discovers it’s Alice who has stabbed an attempted rapist to death in self defence, who was painting her. Frank decides to hides the truth that Alice is the killer but is soon targeted for blackmail by someone else who has found out.

It’s a very good, more than serviceable plot, with similarities to Hitchcock’s first real thriller The Lodger (1927), defining and honing his themes and style that would serve him well for the next four decades. Based on Charles Bennett’s play, the screenplay is by him, an unusually credited Hitchcock, Benn W Levy and Garnett Weston.

Unfortunately, the silent-movie-style performances have dated, particularly as the actors are all too evidently having problems with the primitive sound-recording system. German-Czech star Ondra’s heavily-accented voice was simultaneously dubbed live by British actress Joan Barry.

This is generally acknowledged as the first instance of one actor’s voice being dubbed by another. Nevertheless, Ondra emerges well from this, an effective presence in a purely physical performance.

Despite some overacting, the film still works overall as a highly entertaining, exciting experience. The story and the visuals, plus a clutch of classic Hitchcock sequences, particularly the final chase in the British Museum, and a series of innovative touches, especially the repeated use of the word ‘knife’, mean that it’s still essential viewing.

Shot as a silent in a superior 76-minute version that still exists (2012 restoration), it was re-shot in part as an 85-minute semi-talkie by an adventurous (and sneaky) young Hitchcock (unknown to the studio) to take advantage of the new technology. In this version, the first 20 minutes are disconcertingly silent, that is if you’re expecting a talking picture, and the movie has to work its spell through Hitchcock’s imaginative use of lighting and camera work, which it duly does. The lapses into silent scenes later seem odd and slightly jarring too, before the brio British Museum climax in sound.

Sam Livesey plays The Inspector in the silent version, but Harvey Braban replaces him in the talkie.

Director Michael Powell claims to have suggested the use of The British Museum as the location for the final pursuit, thus beginning Hitchcock’s use of famous landmarks in his chase films. For this sequence, Hitchcock used a process developed by German cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan. It involved taking still photos of the museum interior, then reflecting the photos in a mirror with parts of the silvering of the mirror scraped away to allow people, for example entering through a door, to be filmed through the mirror so they appeared to be in the museum.

Ironically, the silent version did much better business than the sound one, as few cinemas outside big cities were equipped for sound.

Hitchcock’s cameo is being bothered by a small boy on the underground.

The cast

The cast are Anny Ondra as Alice White, Sara Allgood as Mrs White, Charles Paton as Mr White, John Longden as Detective Frank Webber, Donald Calthrop as Tracy, Cyril Ritchard as artist Mr Crewe, Hannah Jones as landlady, Harvey Braban as the Chief Inspector (sound version), Sam Livesey as the Chief Inspector (silent version), Jacque Carter as boy, Johnny Butt as Sergeant, Phyllis Konstam as gossiping neighbour, Phyllis Monkman as gossip woman, Percy Parsons as crook, and Joan Barry as Alice White (voice).

Blackmail is directed by Alfred Hitchcock, runs 85 minutes (sound) or 76 minutes (silent, 2012 restoration), is made by British International Pictures (BIP), is distributed by Wardour Films (UK) Sono Art-World Wide Pictures (US), is written by Alfred Hitchcock and Benn W Levy, based on the play Blackmail by Charles Bennett Produced by John Maxwell, is shot by Jack E Cox, is scored by Jimmy Campbell and Reg Connelly

Release date 28 July 1929 (UK).

© Derek Winnert 2013 Classic Movie Review 444 derekwinnert.com

Link to Derek Winnert’s home page for more film reviews: http://derekwinnert.com/