Chimes at Midnight [Falstaff, Chimes at Midnight] ****½ (1965, Orson Welles, John Gielgud, Jeanne Moreau, Keith Baxter, Margaret Rutherford) – Classic Movie Review 2384

Writer-director-star Orson Welles finally realises a long-cherished pet project in 1965 in grand style with a little help from his friends John Gielgud, Jeanne Moreau, Keith Baxter and Margaret Rutherford– a film of his stage adaptation of the Falstaff scenes of Henry IV Parts 1 and 2 with interpolations from three more of Shakespeare’s plays including Henry V, Richard II and The Merry Wives of Windsor.

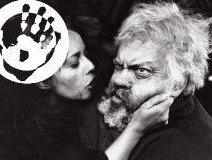

Welles’s own playing of Shakespeare’s Sir John Falstaff is superb, a melancholy giant of a man reduced by circumstances, just like we are given to imagine Welles supposed himself to be. Falstaff is the roistering drinking companion to the young Prince Hal around 1400-13.

The plot centres on Falstaff’s father-son relationship with Prince Hal, who must choose between loyalty to him or to his father, King Henry IV. Welles said the theme is the betrayal of friendship.

In 1939 Welles produced a Broadway stage adaptation of nine Shakespeare plays called Five Kings. In 1960, he revived this project in Ireland as Chimes at Midnight, his final on-stage performance. Still obsessed with Falstaff, he turned the project into a film but he struggled to find financing and lied to producer Emiliano Piedra about intending to make a version of Treasure Island for him instead.

Welles shot Chimes at Midnight throughout Spain between 1964 and 1965, and it was shown in Spain on 22 December 1965 before its official premiere at the 1966 Cannes Film Festival, where it won two minor awards, the 20th Anniversary Prize and the Technical Grand Prize.

Though it failed to win the Palme d’Or, the film is magnetically dark, sad, wise and compelling. It is handsomely made, despite budgetary restrictions, on the Spanish locations, with striking black and white cinematography by Edmond Richard, and beautiful production designs for a real-looking late-medieval England.

The film’s most famous and influential sequence is the harrowingly staged Battle of Shrewsbury, but only about 180 extras were available and Welles used camera and editing techniques to give the appearance of armies of thousands. The score is by Angelo Francesco Lavagnino, who also worked with Welles on Othello.

Gielgud as King Henry IV, Moreau as Doll Tearsheet, Baxter as Prince Hal, Rutherford as Mistress Quickly and Norman Rodway as Hotspur are all splendid, filling in any of the gaps left by Welles’s large turn with resonant, and often touching performances.

Welles directs with sweep, style and imagination, but doesn’t show off and let his imagination run away with him. It ends up as one of his best films, certainly the best of the last 27 years of his life, at least after Touch of Evil.

Ralph Richardson is the narrator in dialogue taken from the works of chronicler Raphael Holinshed. Also in the cast are Alan Webb (Shallow), Marina Vlady (Kate Percy), Fernando Rey (Worcester), Walter Chiari (Mr Silence), Michael Aldridge (Pistol), Tony Beckley (Ned Poins), Jeremy Rowe (Prince John) and Keith Pyott.

On 27 February 2015 it was reported that an almost pristine, uncut 35mm print of Chimes at Midnight had been discovered tucked among tens of thousands of pounds of film elements. The seven reels have gone to a film lab for digital processing.

‘It’s my favourite picture, yes,’ said Welles. ‘If I wanted to get into heaven on the basis of one movie, that’s the one I would offer up. I think it’s because it is to me the least flawed; let me put it that way. It is the most successful for what I tried to do. I succeeded more completely in my view with that than with anything else.’

In 2015 it is re-released in UK cinemas in its 50th anniversary edition, the Filmoteca, Luciano Berriatua restoration. It’s a respectful warts and all film historian’s restoration, not based on using current technologies to provide a quality of picture and sound to better what Welles filmed in the Sixties.

Berriatua said: ‘The most important aspect of this restoration is to make a copy as accurate as possible to the original, with original photography. The most important thing is to play the grading, shadows and contrast selected by Welles. It is not digital restoration in which the image is absolutely clean and no grains or problems. There is a mono sound, as of the time.’

© Derek Winnert 2015 Classic Movie Review 2384

Check out more reviews on http://derekwinnert.com