Heaven’s Gate **** (1980, Kris Kristofferson, Christopher Walken, John Hurt, Isabelle Huppert, Sam Waterston) – Classic Movie Review 95

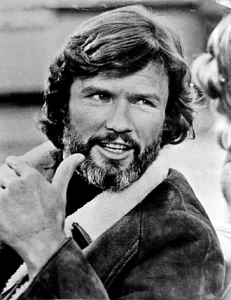

Michael Cimino’s infamous 1980 Western film Heaven’s Gate is the most exciting, most spectacular of visual movies. Christopher Walken’s a knockout. Kris Kristofferson and Isabelle Huppert are excellent.

Directly supervised by director Michael Cimino, the 2013 Director’s Cut and restoration of the 1980 infamous Western film Heaven’s Gate proves a revelation. He’s removed the intermission card and music, and made some judicious scene trims, bringing it in at 216 minutes. The original colour is restored and scratches and blemishes all gone. They’ve made sure this most exciting, most spectacular of visual movies looks great. It looks perfect, then, but is it perfect?

There’s no doubt that it is an epic head-banger of a Western, incredibly long and loud. The images are so brilliantly achieved that you often fool yourself into believing you’re looking at a documentary filmed in widescreen colour in 1890. Those expensively realised scenes are held in view for what sometimes seems an age, but when Cimino finally cuts away from them, you’re actually disappointed, you just want to continue staring in awe.

The three central performances look first rate now. Christopher Walken’s a knockout. Kris Kristofferson and Isabelle Huppert are excellent. The film builds and builds. It’s a long, slow haul but it gets there and the final battle is an absolute stonker!

Back in 1980, the notorious box-office failure of this incredibly costly movie (at more than $40 million) almost sent the Western genre packing off into the sunset and nearly killed off the United Artists studio that backed it (it was saved by James Bond in For Your Eyes Only).

But time has been kind to Camino’s Western. It has started to look like a lost near-masterpiece. It is certainly full of incredibly ravishing stuff, not least Vilmos Zsigmond’s breath-taking cinematography, David Mansfield’s vintage score, the awesome locations (dust-filled towns, snow-peaked backdrops), Tambi Larsen’s set designs and all the millions of lovingly assembled 1890 period props. The last word in tender loving care is prodigiously scattered over every frame of the movie. Everywhere, there’s love and war, and music and dancing.

And, above all, Cimino stages his astonishing epic set pieces with astounding flair and relish. There are unforgettable sequences to admire, like the Harvard graduate dance in the prologue (unsettlingly filmed in Oxford, England, when Harvard refused permission), the roller-skating celebration at the Heaven’s Gate skating rink and saloon, and, especially, that devastating climactic massacre, with its hints of The Wild Bunch and Soldier Blue. Cimino knows and loves his Westerns. That shows.

The characters and performances that once seemed dull now seem moving and effective. The film centres on three main characters – rich, Harvard-educated rogue federal marshal Jim Averill (Kris Kristofferson), crazed, love-struck gunman Nate Champion (Christopher Walken) and French hooker and local madam Ella Watson (Isabelle Huppert). Both men love the alluring Ella, who obliges by romping about in the buff for everyone’s delight. Their fraught love triangle is effectively played and magnificently set against an archetypal yarn of the clash between Wyoming’s immigrant settlers and evil empire builders.

Under-playing just right, Sam Waterston makes a fantastic, chilling villain as Frank Canton, the coldly ruthless head of the Wyoming Cattle Owners’ Association, who meet and draw up a death list of 125 folk they are going to shoot, and raises a posse to start the work. The lawman Jim isn’t impressed, especially when he gets a copy of the list and it includes his girlfriend (and of course true love, though he can’t express it) Huppert, who has stupidly accepted rustled cattle in return for sexual favours in the cheerful brothel she runs. Nate works as a mercenary for the Cattlemen’s Association. He’s got just the right temperament and moustache for it. But he’s a loose cannon too.

Less successfully, John Hurt plays Jim’s old college buddy, now with the Cattlemen’s Association too, and Jeff Bridges is the (I think) Scandinavian owner of the Heaven’s Gate saloon. Their parts are tricky to play, none too well developed, and slightly defeat these two fine actors. Brad Dourif, Joseph Cotten, Geoffrey Lewis (Trapper Fred) and Mickey Rourke don’t have enough to do, but do it well. Great character actor of the period, Richard Masur, is outstanding as Jim’s railroad worker buddy.

Apart from its story of star-crossed lovers, the film has something on its mind too – a big theme, the power of the rich against the poor, and the racist oppression of the powerful against the foreign (European) immigrants flooding into the developing nation of the time. It’s a hugely ambitious, stonkingly achieved portrait of a society utterly in chaos, broken down by greed and hate. A dramatic, evergreen story, then, backed by a fine, noble theme.

Cimino plays fast and loose with the facts of the real-life bloody 1892 Johnson County War, alienating some Western fans. But this is only a film, not a documentary after all.

And, finally, for a ‘failure’, Heaven’s Gate now stakes its claim to being a stupendous achievement.

After its original showing in 70mm prints in 1980 at its then 219 minutes, Cimino cut it by 70 minutes on general release in 1981 (to 149 minutes), removing the prologue (which is essential to understanding the story) and epilogue, but the full version is way more magnificent, especially now it is restored and finessed in the Director’s Cut.

In 1980 it was picketed in London by animal rights activists concerned over the ill-treatment of horses in the film. With horses and chickens allegedly misused, the US authorities tightened up their controls on film-making involving animals.

Originally titled The Johnson County War, it was given the go-ahead after Cimino’s The Deer Hunter swept the board at the Oscars, winning five Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. Most of the filming was done in Montana; none in a studio. Shooting took 165 days, with 2,500 extras employed. Composer David Mansfield is the violinist at the roller-skating celebration.

Michael Cimino (February 3, 1939 – July 2, 2016)

After a five-year gap, Cimino was able to resume work with Year of The Dragon; followed by The Sicilian and Desperate Hours; his last film is The Sunchaser in 1996. After that, Cimino became reclusive; spending most of the last two decades of his life in his home in Beverly Hills writing constantly.

Vilmos Zsigmond (June 16, 1930 – January 1, 2016)

Vilmos Zsigmond died on January 1 2016, age 85. He was known for his use of natural light and vivid use of colour on films like The Long Goodbye (1973) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), for which he won the Oscar for Best Cinematography. He was also nominated for The Deer Hunter (1978), The River (1984) and The Black Dahlia (2006).

Kristoffer Kristofferson (June 22, 1936 – September 28, 2024)

© Derek Winnert 2013 Classic Movie Review 95

Check out more reviews on http://derekwinnert.com/