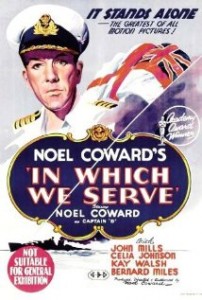

In Which We Serve ***** (1942, Noël Coward, John Mills, Richard Attenborough, Celia Johnson, Kay Walsh) – Classic Movie Review 1676

Noël Coward’s inspired 1942 moral-boosting war movie In Which We Serve is a polished gem that comes only from a true labour of love.

‘This is the story of a ship…’

Noël Coward’s inspired 1942 moral-boosting war movie In Which We Serve is a polished gem that comes only from a true labour of love. The film is arguably Coward’s finest achievement in the movies, as star, writer, co-director, co-producer as well as composer of his tour-de-force classic movie. As it is such a different kind of film, it is impossible to compare it for quality with Coward’s other triumphs, Blithe Spirit and Brief Encounter, so we shan’t even try.

Coward’s great achievement is a most stirring tribute to the British Royal Navy, the British bulldog wartime fighting spirit, and particularly to Lord Louis Mountbatten and the men of the torpedoed destroyer HMS Kelly, on whose desperate real-life story the film is based. But here it’s the British destroyer HMS Torrin, whose story from its construction to its sinking in the Mediterranean during action in World War II is told in flashbacks by the British survivors as they cling to a liferaft.

Coward’s star role is unforgettable and deserves more attention and respect than it gets. Indeed, that’s true of the film as well. His all-time great performance as Captain E V Kinross RN, the skipper of the destroyer, based on his friend Lord Mountbatten, is noble and retrained, while his characteristic writing is perfect for the piece, warm, realistic and amusing.

In Which We Serve is partly a technical and logistical triumph. It is beautifully crafted in all departments, and Coward won a hugely deserved special honorary Oscar for his outstanding production achievement. He was also Oscar nominated for Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay and it is a huge shame he didn’t win either. However, the New York Film Critics voted it their year’s Best Film. It is filmed at Denham Studios, Buckinghamshire, and on location in Plymouth (Devon), Portland (Dorset) and on Dunstable Downs (Hertfordshire) for the picnic scene.

It marks the film débuts of Celia Johnson, who plays Kinross’s wife, young Daniel Massey, baby Juliet Mills and the 19-year-old Richard Attenborough as Young Stoker. In other supporting roles a young John Mills plays Ordinary Seaman Shorty Blake, Bernard Miles plays the kindly Chief Petty Officer Walter Hardy, Joyce Carey portrays his wife Kath, plus Kay Walsh, Michael Wilding, Kathleen Harrison, Leslie Dwyer, James Donald, Frederick Piper, Wally Patch, Walter Fitzgerald, Ann Stephens and many others.

It is the directorial debut for both Coward and David Lean, who scored his first director credit co-directing with Coward, who, because had no experience in making films, called for help from the best technician around at the time. Lean’s expertise as an editor no doubt helps to make it all so smooth and polished.

However, it is said that Coward initially wasn’t at all thrilled when Lean insisted on a co-director credit. Before accepting the job, Lean asked Coward how the credits would read. Coward suggested that they would say ‘helped by David Lean’ but Lean insisted that they should read ‘directed by Noël Coward and David Lean’. Coward agreed reluctantly or readily depending on which version of the story you believe.

In any case, they seem to have worked together remarkably smoothly for two men with big egos and later Coward was so delighted with the finished movie that he was generous enough to promise Lean a chance to direct his every script after that. Their fruitful classic partnership went on to produce This Happy Breed, Blithe Spirit and Brief Encounter.

Celia Johnson, Everley Gregg and Joyce Carey all memorably re-appear in Brief Encounter. Celia Johnson, Kay Walsh and John Mills all memorably appear in This Happy Breed.

© Derek Winnert 2014 Classic Movie Review 1676

Check out more reviews on http://derekwinnert.com/