Like Someone in Love **** (2012, Rin Takanashi, Tadashi Okuno, Ryô Kase) – Movie Review

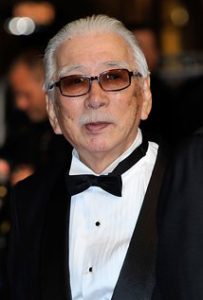

The title of 73-year-old Iranian-born cinema master Abbas Kiarostami’s 2012 Tokyo-set drama comes from an Ella Fitzgerald song played at a pivotal moment in the movie. His original title was The End, which considering the way the film ends is all wrong. But Like Someone in Love is perfect as a title. And it’s perfect as a movie too. The Japanese-language film, written and directed by Kiarostami, was selected to be screened in the main competition section at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival.

‘There is nothing determined and definitive about love,’ says Kiarostami. ‘It’s better to say that we are Like Someone in Love rather than asserting that we are in love. Death or birth are definitive. Love is nothing but an illusion. We have four people in this film who are we are like some people in love.’

The quartet are: (1) Akiko, a pretty but slightly distant sociology student who works nights as a high-class escort. (2) Takashi, her latest client, a retired sociology professor, who she reluctantly dumps meeting her Gran for, spending the night with him and next day allowing him to drive her to university where she has an exam. (3) Noriaki, her volatile boyfriend, whom they meet outside the uni, with the boy assuming the kind old professor is Akiko’s grandfather and (4) the old man’s neighbour, who still keeps a flame burning for him.

A game of odd role-playing begins, with the focus shifting from the girl to the old man to the boy, and it’s clear that, though the professor plays the game loyally so the girl’s other game will not be revealed, the hoax must surely eventually be discovered. And then what?

That is all there is of this film. It’s not about story at all, only character and mood and place. So it’s hardly even to be called a drama, just a vignette. A miniaturist fragment. But it’s superb. Beautifully, lovingly, exquisitely crafted, it pulls you in to the tension of its relationships. There’s no clue where it’s going, just like with life itself. And Kiarostami’s neo-realist filming method is a marvel, at once both realistic and stylised, with a vibrant you-are-really-there-feel, especially in the driving sequences, but also in the bar at the start and the professor’s flat later on.

Kiarostami’s proud that he’s ‘unable to be a real story-teller’. This may well frustrate some audiences. But most art-house film lovers will quietly thrill to this demonstration of Kiarostami’s idea ‘that we can never be the witness of a story from its beginning to the end.’ He continues: ‘I would say that this film doesn’t have an adequate opening and it doesn’t have a real ending either. But it also proves my idea that all films start before we get into them and end after we leave them.’

This does prove a slight hiccup at the start as you’re disoriented by not knowing who’s conversation you’re supposed to listen to at the bar and again at the end when the film ends abruptly, making you want to see the sequel immediately. But, the point is, it works, or at least Kiarostami makes it work. I don’t recommend this method to other, younger, less brilliant film-makers. Let’s have the whole story, guys, clear and simple, that’s what we pay for. But, as I said at the start, Kiarostami’s a master. Such an artist can make his own rules, cheerfully break any already laid down, and no one will complain. Brilliance is its own reward.

Dazzled by Kiarostami’s script and direction, I forgot to mention the acting. Rin Takanashi is Akiko, Tadashi Okuno is Takashi, Ryo Kase is Noriaki, Mihoko Suzuki is the old man’s neighbour. All are perfect, but is one has to be singled out it must be the 82-year-old Okuno, giving a performance of haunting grace. Ironically, though, at the wheel in a road movie around Tokyo, the actor can’t actually drive!

Abbas Kiarostami died on 4 July 2016 after a battle with cancer, aged 76.

© Derek Winnert 2013 Movie Review

Check out more reviews on http://derekwinnert.com