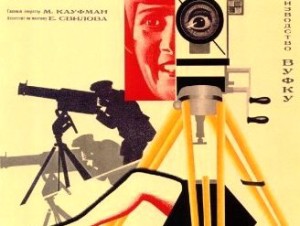

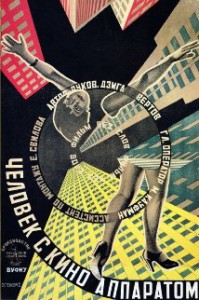

Man with a Movie Camera [Chelovek s kino-apparatom] ***** (1929) – Classic Movie Review 2749

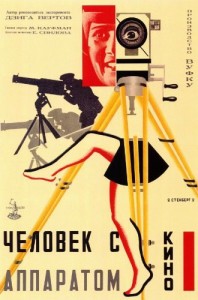

‘I am the camera eye. I am the mechanical eye. I am the machine which shows you the world as only I can see it.’ Director Dziga Vertov’s influential, light-hearted, fascinating 1929 Russian abstract documentary is inventive and influential.

Quite mesmerising to watch, this Soviet avant garde film dazzles the eye with its provocative images and sheds light on the vibrant Russian urban life of the era. It’s a dynamically energised ode to a newly industrialised world, depicting a high-octane modern metropolis invigorated by an increasingly industrialised economy.

In his first and best-known feature, he as director and editor and his cameraman Mikhail Kaufman (who is seen repeatedly throughout the film as the Man with the Camera) show off all the camera’s possibilities such as montage, slow motion, fast motion, freeze frame and split screen. Even the editing of the film is depicted, though, playfully, we don’t seem to see any of the footage the cameraman is apparently shooting.

In an investigation of the nature of film itself, the experimental film is narrative free and stripped of the conventions of silent cinema, having no actors nor inter-titles, though it is divided into six numbered 10 to 12-minute chapters that nevertheless have no name or stated theme.

With all the advances in cinema over the intervening years, it is perhaps hard now to understand the astonishment this caused in 1929. But we can still sit in amazed awe as we take in Vertov’s infectious enthusiasm and relish the startling images of life in Moscow’s streets, trains, beach, interiors and so on.

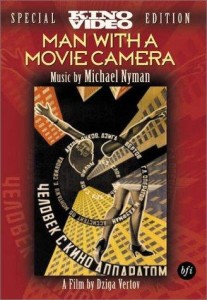

It was released as a silent movie, accompanied in cinemas by live music. Michael Nyman composed a notable score to accompany it (available on DVD) and the British electronic/jazz Cinematic Orchestra created a soundtrack released in 2003 as the Man with a Movie Camera album and played it live at film festivals over the world.

But in 2015 the film is showing in UK cinemas again newly restored, and it now has a dynamic and exciting abstract score by the US-based Alloy Orchestra, based on Vertov’s own extensive notes with help from film scholars Yuri Tsavian and Paolo Cherchi Usai.

It was shot over three years, in Odessa, Ukraine, Moscow, Kiev and Kharkiv.

It was voted Number One in Sight & Sound’s 2014 poll of the greatest documentaries of all time, and Number Eight in Sight & Sound’s 2012 poll of the greatest films of all time. Its influence can be seen in the work of Jean-Luc Godard, Chris Marker and Godfrey Reggio with the film Koyaanisqatsi (1982).

© Derek Winnert 2015 Classic Movie Review 2749

Check out more reviews on http://derekwinnert.com