Mon Oncle [My Uncle] ***** (1958, Jacques Tati, Jean-Pierre Zola, Adrienne Servantie) – Classic Movie Review 2411

In the first of his films to be released in colour, co-writer/director/star Jacques Tati is working confidently, imaginatively, inventively and successfully at around the peak of his comic ingenuity and cleverness. Honoured by Hollywood with the 1959 Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, the film received more honours than any of Tati’s other movies.

After Jour de Fete and Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday, Tati again re-creates his iconic endearingly bumbling character of Monsieur Hulot, who comes up against all things modern and mechanical in a great display of pantomime comedy that bears comparison with the vintage silent movies of Charles Chaplin and Buster Keaton.

The film’s theme is Monsieur Hulot‘s struggle against postwar France’s infatuation with modern architecture, mechanical efficiency and consumerism in a late-50s society that had recently embraced a wave of industrial modernisation.

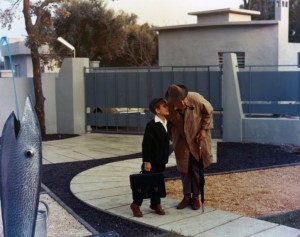

This time Monsieur Hulot lives a spare but contented existence, but clashes with the modern world reflected in his sister’s family’s absurdly à la mode life. He is the adored uncle of the nine-year-old Gérard Arpel (Alain Bécourt), who lives with his materialistic parents, Monsieur and Madame Arpel (Jean-Pierre Zola, Adrienne Servantie), in an ultra-modern geometric house and garden, the Villa Arpel, in a new suburb of Paris.

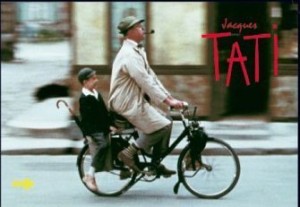

Everything is fully automated and the boy is raised in a similar fashion. Monsieur Hulot, however, is a free spirit, lives in an old, run-down city district, is unemployed, and gets around town either on foot or motorised bicycle.

Gérard, bored by the sterility and monotony of his life with his parents, relishes the company of his uncle, who bonds with him easily as he is little more than a child himself. To take away the influence of the uncle on their son, the Arpels scheme to saddle him with family and business responsibilities and his brother-in-law gets Hulot a job in the plastics factory he manages.

In a tour de force of ingenuity, Tati keeps this single thought of the sterility of modern life going in an apparently endless stream of inventive visual jokes and ideas. A major feature of the film is its superb design, with the astounding superficially beautiful yet sterile sets designed by Jacques Lagrange.

The star often peripheralises himself to what’s happening on screen and the film is virtually silent, with the dialogue barely audible and largely subordinated to being a sound effect. Noises of arguments and banter complement other sounds, with the music used to characterise environments.

The film won the Jury Special Prize at the 1958 Cannes Film Festival, the French Syndicate of Cinema Critics voted in Best Film in 1959 and the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

The full original French release in 120 minutes but the cut international version runs to 111 minutes. The English-language version of the film, nine minutes shorter than the original and released as My Uncle, was filmed at the same time as the French-language version.

There are slight differences in the staging of the scenes and in the performances. In the English-language release, French signs are replaced by ones in English and important dialogue is dubbed in English, although background voices remain in French.

The film was another big success for Tati, with 4,576,928 admissions in France, but it was denounced there by some critics as having a reactionary view of the emerging French consumer society, though this criticism soon crumbled in the face of the film’s huge popularity in France and abroad.

The sets were built in 1956 at Studios de La Victorine, now known as Studios Riviera, near Nice but taken down after filming.

Jour de Fete, Tati’s first full-length film, was filmed in colour but released in black and white through technical issues, though we now have a restored full colour version.

© Derek Winnert 2015 Classic Movie Review 2411

Check out more reviews on http://derekwinnert.com