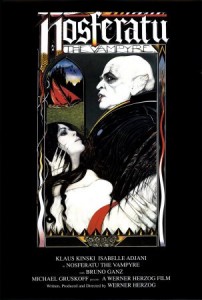

Nosferatu the Vampyre [Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht] **** (1979, Klaus Kinski, Isabelle Adjani, Bruno Ganz) – Classic Movie Review 238

‘The Master is coming.’ – Renfield.

‘Cruel is when you can’t die even if you want to.’ – Dracula.

Director Werner Herzog triumphantly remakes the famous 1921 horror silent with all due respect to the original and exactly the right actors. With its unforgettable vampire brilliantly brought back from the undead, this 1979 gothic classic is recognised as a second masterwork of the movie nightmare.

Herzog sticks surprisingly closely to the original film, changing very little apart from using the Bram Stoker Dracula character names that F W Murnau couldn’t in 1921 for copyright reasons. (He was sued successfully anyway.) He keeps the Murnau ending, which hinges on a woman pure of heart being able to destroy the monster by tempting him to stay beyond cock crow and not notice the fatal daylight.

Obviously Herzog has colour and sound at his disposal this time, and he deploys them in the most peculiar, unsettling and imaginative way. Nothing about this movie (or any other Herzog film) is ordinary.

If this remake is at heart a tribute to the original Nosferatu, Herzog also makes it as a salute the silent movies in general, with long wordless passages and extravagant silent-movie acting, especially from lady in peril Isabelle Adjani. At the same time, it’s a European art film, very much a Herzog movie, the work of an individual, idiosyncratic auteur, with links to his other films like Aguirre.

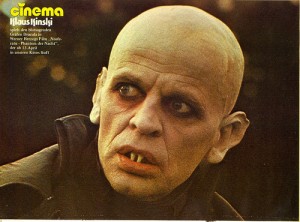

Taking his acting cue and look entirely from Max Schreck, Klaus Kinski is perfect, looking (with the help of four hours in the makeup chair a day) nightmarishly ravaged and scarily crazed as the desperately undead vampire Count Dracula. As the star, he gets a fair old bit more to do than his predecessor, Max Schreck. His detailed playing of the role is extraordinary and involving, and provides the movie’s backbone.

But the handsome young Bruno Ganz and the toothsome, wide-eyed Adjani have more screen time than Kinski and both do compelling work as Jonathan Harker and his new young wife Lucy. Ganz is a compelling, tormented hero and Adjani effectively (and sometimes amusingly) accesses the extremes of silent film acting for her high-anxiety performance.

Herzog said he wanted to stay close to the Bram Stoker novel, but he’s way nearer to the original Murnau film, unsurprisingly since he partly used Henrik Galeen’s original 1921 screenplay to write his own. It’s noticeable that neither Stoker nor Galeen are credited, just Herzog.

The plot is identical to the 1921 version. Happily married to Lucy, Jonathan is an estate agent in Wismar. His mad, giggling boss Renfield (an abrasive, increasingly irritating Roland Topor) sends him to Transylvania to sell a house near his own in Wismar. to Count Dracula. Lucy tries to stop him but he sets off on his four-week journey. Transylvanian locals at an inn warn him to go no farther and he has to walk the last stage of the journey.

At the castle, he’s greeted by the eerie-looking, rat-like Count, a rather ugly specimen with a white, bald head, dark-rimmed eyes, two pointy teeth, huge ears and long, gruesome talons. Dracula offers him food and drink, but gets way over-excited when he cuts a finger and sucks his blood. And then even more way over-excited when he sees a pendant portrait of Lucy.

Drac loads a cargo of coffins, gets in one and sets sail from the nearby Baltic port of Varna and heads for Wismar. Jonathan escapes from the castle and chases after him to try to save Lucy.

Hoards of rats leave Drac’s ship after his arrival in Wismar, run ashore and start a Black Death plague in the city. When Jonathan returns and is reunited with Lucy, he’s sick and semi-catatonic. Lucy’s realised what’s happened and what she must do.

Thanks in part to the performances and the film’s gothic charms, it’s a thrilling, atmospheric, well-paced movie. It has the advantage over the 1921 film with the bonus of Jorg Schmidt-Reitwein’s ravishingly weird, grainy-looking Eastmancolor cinematography and an oddly unsettling choice of sound and music as Herzog accompanies his images with Wagner, Popul Vuh and Florian Fricke.

The 2013 restoration shows what an exciting looking movie it is, with outstanding work on production design by Henning von Gierke, makeup by Reiko Kruk and costume design by Gisela Storch.

It’s a strange mix, but somehow it all works.

Maybe there’s a bit too much of the rats and the Black Death and Adjani wandering around towards the end, taking the focus away from the main plot and Dracula, but it’s a only a minor fault. Herzog typically got carried away with his rats, 10,000 of them transported from a laboratory in Hungary in a folie de grandeur. The white rats were dyed grey for the film and Herzog got involved in all the details of that too. He swears that, though the rats were controversially released in the town, they were all caught and caged, and he never lost a single rat.

It’s generally seen everywhere now in the original German, subtitled version after the simultaneously filmed English language version proved unsatisfactory. Huppert seems to be speaking French and poorly dubbed. Restored and re-released in 2013, it looks considerably better than it ever did and has worn astonishingly well, seeming far better than ever.

Delft stands in beautifully for Wismar.

Kinski won the Best Actor award at the 1980 German Film Awards. Henning von Gierke’s outstanding production design won the Silver Bear at Berlin in 1979. Kinski’s makeup was by the Japanese expert Reiko Kruk and the delicious costume designs by Gisela Storch.

You may have noticed the Mina and Lucy characters are reversed from Stoker’s version.

The slo-mo bat shots are documentary footage.

Herzog, who has a cameo sticking his foot in a coffin and getting bitten by a rat, has the last word: ‘I feel the vampire genre is one of the richest and most fertile cinema has to offer. There is fantasy, hallucination, dreams and nightmares, visions, fear and, of course, mythology.’

http://derekwinnert.com/nosferatu-a-symphony-of-horrors-classic-film-review-237/

© Derek Winnert 2013 Classic Movie Review 238

Check out more reviews on http://derekwinnert.com