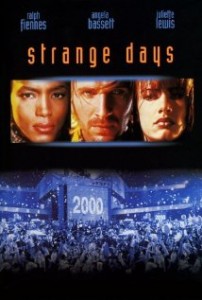

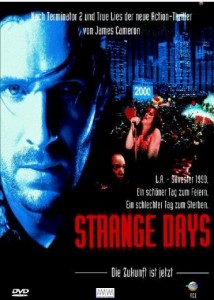

Strange Days *** (1995, Ralph Fiennes, Angela Bassett, Juliette Lewis, Tom Sizemore) – Classic Film Review 760

Britain’s Ralph Fiennes is oddly cast as American ex-cop turned cynical cyberpunk Lenny Nero in a sea of troubles in director Kathryn Bigelow’s nastily violent ‘apocalypse soon’ sci-fi thriller, made in 1995 but set cannily on the very eve of the then impending 21st century.

The movie has an intelligent veneer but merely dabbles with ideas like virtual reality and its cynically apocalyptic near-future vision, while exploitatively using sensitive issues and explosive real events like the LA riots, the King killing and police corruption for iffy action entertainment.

Fiennes’s tacky and tawdry anti-hero, who is illegally selling virtual reality disks which give the experience of all human activity as if at first hand, receives a disk of the rape and murder of one of his disk traders. And then he enlists the help of two friends (Angela Bassett, Tom Sizemore) to track the killer and save his ex-girlfriend (Juliette Lewis), accidentally uncovering a police conspiracy in 1999 Los Angeles.

Bigelow’s direction is slick and flashy, and her portrait of an under-siege collapsing society impressively large scale. But at heart James Cameron’s action thriller story and screenplay (with Jack Cocks) is old fashioned and often careless, with slack plotting, some feeble dialogue, over-length at 145 minutes and an obvious solution to the rapist killer’s identity.

However, propelled with some well-staged action moments and good one-liners, Strange Days is a visceral, sometimes exciting, in-your-face movie with pounding noise levels and scary, intense, disturbing displays of violence, particularly to women.

Bigelow defends her film: ‘Strange Days is provocative. Without revealing too much, I would say that it feels like we are driving toward a highly chaotic, explosive, volatile, Armageddon-like ending. Obviously, the riot footage came out of the LA riots. I mean, I was there. I experienced that. I was part of the cleanup afterwards, so I was very aware of the environment. I mean, it really affected me. It was etched indelibly on my psyche. So, obviously, some of the imagery came from that.

‘I don’t like violence. I am very interested, however, in truth. And violence is a fact of our lives, a part of the social context in which we live. But other elements of the movie are love and hope and redemption. Our main character throws up after seeing this hideous experience. The toughest decision was not wanting to shy away from anything, trying to keep the truth of the moment, of the social environment. It’s not that I condone violence. I don’t. It’s an indictment. I would say the film is cautionary, a wake-up call, and that I think is always valuable.’

She isn’t, but she could be talking about her 2017 film Detroit.

She became the first woman to win an Academy Award for Best Director for The Hurt Locker (2008), which also won her a quarter share in its Best Picture Oscar.

© Derek Winnert 2014 Classic Film Review 760 derekwinnert.com