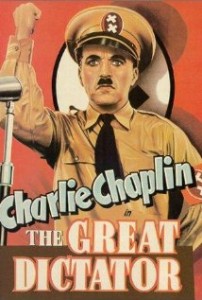

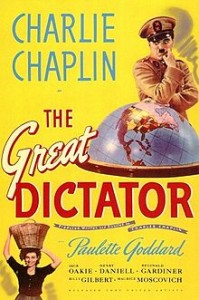

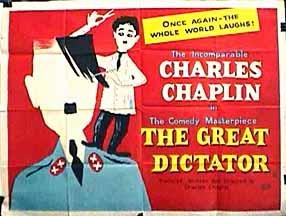

The Great Dictator ***** (1940, Charles Chaplin, Paulette Goddard, Jack Oakie) – Classic Movie Review 1044

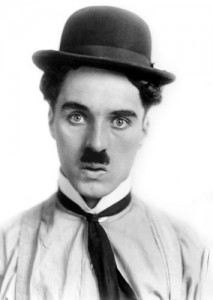

Producer-writer-director Charles Chaplin’s 1940 brave, risky and pioneering satirical comedy classic focuses on a timid Jewish barber who is mistaken for the dictator of Tomania (‘our Fooey’) and then takes over from him. A stirring, controversial condemnation of Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini’s fascism, anti-Semitism and the Nazis, it was Chaplin’s first true talking picture, as well as his most commercially successful film.

At the start of World War Two, before America had joined the conflict, Chaplin commandingly and fearlessly lampoons German leader Adolf Hitler as a vain and ridiculous fool, spouting nonsense. It was the first Hollywood film bold enough to denounce Hitler directly, attacking the Nazis, fascism and anti-Semitism in broad but unforgettable strokes. He mocks the Nazis as ‘machine men, with machine minds and machine hearts’.

In the story, the poor Jewish barber is trying to avoid persecution from dictator Adenoid Hynkel’s regime, while the latter bids to expand his evil empire.

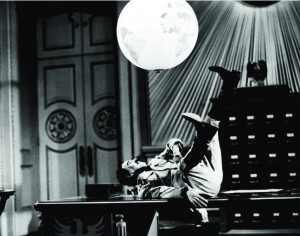

It was Chaplin’s his first full-sound film a dozen years after the talkies took off, though even here the dialogue is quite spares and he reverts back to the pantomime old-style Chaplin in some of the film’s best-recalled, fondest remembered vintage sequences – for example Chaplin as the barber shaving a customer to Brahms’ Hungarian Dance No. 5 or as Adenoid Hynkel dancing with a globe-balloon.

The score is written and directed by Meredith Willson, later to become well known as creator of the 1957 musical comedy The Music Man. He was modest enough to credit Chaplin generously: ‘I got the screen credit for The Great Dictator music score, but the best parts of it were all Chaplin’s ideas.’

Chaplin adopts a cartoonish style, talking nonsense to imitate Hitler’s rabble-rousing speeches at rallies or partnering Jack Oakie’s equally successful spoof of Italian leader Benito Mussolini as Benzino Napaloni, Dictator of Bacteria. It’s not exactly subtle but it is funny. While the German spoken by the dictator is complete nonsense, the language the shop signs and posters in the Jewish quarter are written in is Esperanto, created in 1887 by Dr L L Zamenhof, a Polish Jew.

Also heading the appealing, expert cast, Paulette Godard plays the waif Hannah and Henry Daniell is the movie’s co-villain Garbitsch, while Reginald Gardiner, Billy Gilbert, Maurice Moscovich, Emma Dunn, Grace Hayle, Carter De Haven, Bernard Gorcey and Chester Conklin also appear.

The Great Dictator starts with a bold, striking premise, but it is an uneven, slightly patchy achievement as a satirical comedy, though some of it is very funny and clever, and the best of it brilliant. Really only the final six-minute lecture about the need for peace totally doesn’t work when viewed now, though of course it remains historically interesting.

This daring film was Chaplin’s biggest box-office success, though much later in his 1964 autobiography he said he would not have made it if he’d been aware of the Nazi genocidal slaughter of the Jewish people and the actual horrors of the Nazi concentration camps, for the atrocities of the Holocaust weren’t fully known in the US at this time.

There were five Oscar nominations, including three of them for Chaplin, but no wins, surprisingly given its subject and Chaplin’s status in Hollywood. But Hollywood was afraid of politics and didn’t want to be seen supporting Chaplin’s stand against the fascists.

A digitally restored version of the film was released on DVD and Blu-ray by The Criterion Collection in May 2011. The extras feature colour production footage shot by Chaplin’s half-brother Sydney, the deleted barbershop sequence from Chaplin’s 1919 film Sunnyside, and the barbershop sequence from Sydney Chaplin’s 1921 film King, Queen, Joker, in which Sydney earlier played the dual role of a barber and ruler of a country who is about to be overthrown.

Weirdly, Hollywood’s first parody of Hitler was by the Three Stooges in a short film You Nazty Spy!, which premiered in January 1940.

See also To Be or Not to Be (1942), a dark comedy on living in Nazi-occupied Warsaw (remade in 1983 by Mel Brooks), The Producers, Brooks’s 1968 comedy about an attempt to mount a sure-to-fail musical based on an ex-Nazi’s failed play Springtime for Hitler about the ‘glories’ of Nazi Germany, and Life Is Beautiful, Roberto Benigni’s 1997 Italian film about a Jewish Italian who uses his comical imagination to help his family during their internment in a Nazi concentration camp.

© Derek Winnert 2014 Classic Movie Review 1044

Check out more reviews on http://derekwinnert.com/