This Sporting Life ***** (1963, Richard Harris, Rachel Roberts, Alan Badel, William Hartnell) – Classic Movie Review 190

All-time great British director Lindsay Anderson’s searing film This Sporting Life is an authentic British classic of the short-lived but influential and vibrant 60s realist new wave movement. Kitchen sink drama, it was called back then. It captures the mood and spirit of the time (1963) and place (Northern England) and has the enormous benefit of providing a perfect showcase for knockout, Oscar-nominated performances from Richard Harris and Rachel Roberts.

It is Harris’s first starring role, winning him the Best Actor Award at the 1963 Cannes Film Festival, while Roberts won her second BAFTA award. It opened at the Odeon Leicester Square in London’s West End on 7 February 1963 but soon the boss of the Rank Organisation was calling it a ‘squalid’ film.

Working from his own brilliant, semi-autobiographical source novel, David Storey, a regular collaborator with Anderson in the theatre, provides a wonderful script, which Anderson grabs hold of eagerly to create a highly emotional, gut-thumping experience rare in British cinema.

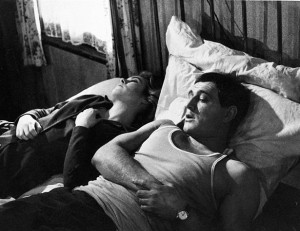

Anderson and Storey would hate me to say this, but it’s the acting you best remember. In all his long and variable career, Harris was never better than as Frank Machin, the Northern English coal miner who becomes a star in the rugby league team run by his silkily slimy employer, Gerald Weaver (Alan Badel). Machin’s a boarder in the house of Mrs Margaret Hammond (Roberts), a respectable widowed landlady whose husband was killed in Weaver’s mines. It’s set in Wakefield, though not named as such.

Machin is tough and ambitious, but his shocking mean streak comes to the fore as he becomes increasingly desperate and brutish both as a rugby player and as Mrs Hammond’s lover. If he’s an angry young man, he’s really not a very nice one at all. Somehow, Harris keeps him just this side of sympathetic, though it’s close, and by the end you simply feel sorry for him. He’s just another sad and pathetic victim of the system.

Working like a beaver on acid to create the kind of incredibly emotional, gut-thumping experience hardly ever seen in British movies, an inspired Anderson doesn’t pull his punches in his feature film debut. He gleefully grabs hold of the characters and story by the scruff of their necks and pushes them to their limit and beyond, while bullying his distinguished actors into new high levels of their work. The film’s hard-blow impact is helped enormously by Denys Coop’s immaculate black and white cinematography, particularly in the thrillingly urgent shots on the sports field which have a documentary feel to them, and by the incisive film editing of Peter Taylor.

This is as penetrating an examination of failure, loss and pain at the bottom end of the barrel as we’ve ever seen on a British screen. But if that seems gloomy and depressing, the film goes for an entirely hopeful message at the end. We mustn’t be like these doomed, destructive characters. It’s our duty to connect with and love one another. It’s a bit late in the day for uplift, but better late than never. No doubt the film’s downbeat nature did it no favours at the box office.

Roberts is amazing in a heartbreaking turn and it’s fantastic to see the athletic young Harris at his absolute acting peak. There’s a vintage Equity roll call for the support cast. William Hartnell as the coach ‘Dad’ Johnson, Arthur Lowe as the bossy team owner Charles Slomer, Leonard Rossiter as the sports writer, Frank Windsor as the dentist, Wallas Eaton as the waiter, Peter Duguid as the doctor, Colin Blakely, Vanda Godsell, Anne Cunningham, Jack Watson, Harry Markham and George Sewell (his debut) are all essential to the cast. It’s even worth seeing just for them.

The producer-distributors, the then all-powerful Rank Organisation, had no faith in it and effectively dumped it, killing its commercial chances and consigning to art house cinemas, where at least it was honoured and respected. It did not recoup its cost, prompting John Davis, chairman of the Rank Organisation, to announce his company would make no more kitchen sink films and would never make such a ‘squalid’ film again. It proved a turning point, ending UK producers’ willingness to back British New Wave films.

It is Anderson’s first feature as director, after winning an Oscar for his documentary short Thursday’s Children (1954). The Rank Organisation first had in mind Joseph Losey, then Karel Reisz who thought the material too similar to his Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) and suggested Anderson direct it while he produce it.

Scenes were filmed at the Wakefield Trinity rugby league club’s stadium, Belle Vue, and at the Halifax stadium Thrum Hall. The houses were in Servia Terrace in Leeds. The riverside location is Bolton Abbey in the Yorkshire Dales. The bus scene was filmed at the top of Westgate, Wakefield.

It is Glenda Jackson’s debut (as one of the singers round the piano at the Christmas party), Anton Rodgers is a customer at the restaurant and Edward Fox (also his debut) is its barman. Storey has a cameo as one of the rugby players.

The full film runs 134 minutes but the cut version runs at 129 minutes.

Lowe and Cunningham were in Coronation St together at the time of filming. Hartnell was hired as the first Doctor Who after the show’s producer Verity Lambert saw this.

Hundreds of wooden dummies of spectators can be seen filling in the crowds at the rugby scenes at Belle Vue. But there’s so much realism in the film. Encouraged by Anderson, real-life rugby league legend Derek Turner was to punch Harris in the scrum dust-up, and he knocked him out completely ending the day’s filming for Harris to recover.

Limerick-born Harris himself was a real-life rugby player, but of rugby union, and a lifetime fan.

Anderson wrote in his diary: ‘The most striking feature of it all, I suppose, has been the splendour and misery of my work and relationship with Richard. I ought to be calm and detached with him. Instead I am impulsive, affectionate, infinitely susceptible.’

British film, theatre and documentary director, and film critic Lindsay Gordon Anderson (17 April 1923 – 30 August 1994) is remembered for This Sporting Life, his 1968 film If.., O Lucky Man!, In Celebration, Look Back in Anger, Britannia Hospital, Glory! Glory! and Is That All There Is?.

© Derek Winnert 2013 Classic Movie Review 190

Check out more reviews on http://derekwinnert.com/